In the contemporary context of cultural, historical, economical, and societal transformations, the design and practice of learning environments is changing both in formal and informal education institutions. Despite the multiples barriers that a school system rooted in 19th and 20th centuries industrial paradigms offers, innovative educators are designing and implementing responsive learning environments to support contemporary literacy practices. Although there are many challenges to the implementation of such kind of environments in formal education, the opportunities for implementing them continue to grow as the new literacy practices become more and more important for contemporary society, culture, and economy.

In Transition towards a Network/Information Society (a.k.a. Networked Advanced Capitalism)

The transition from an industrial capitalist society to a post-industrial informational and networked advanced capitalist society creates a context of change and transformation. All areas of everyday life are changing. Work, learning, entertainment, consumption, production, education, leisure, home, and play are being transformed and their boundaries have become porous. For instance, the consumption of information has turned into production thanks to some of the practices that networked digital media and participatory cultures are fostering such as the creation of remix videos by fans of popular tv shows. In a similar way, peer-based models of production of information such as the one developed by the free software and open source projects tend to blur the distinctions between play and work, labor and fun.

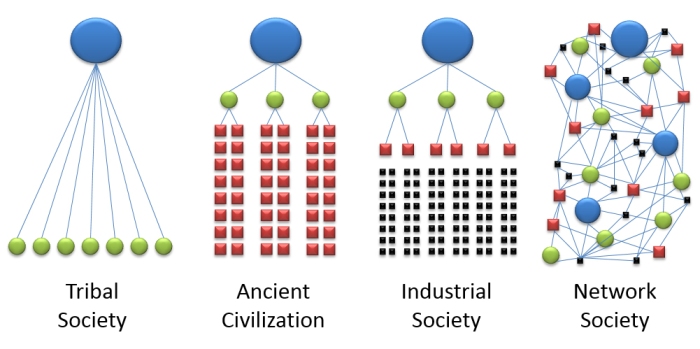

Change, transformation, and transition are the characteristics of our present time in contemporary advanced capitalist societies. They are also characteristics of an increasingly global interconnected world in where networks and networking are the basis for a new logic of production. As Gee (2000) has explained in “New People in New Worlds.: Networks, the New Capitalism and Schools,” the logic of the new capitalism “focuses on change, flexibility, speed, and innovation. In this context, disciplinary expertise goes out of date too rapidly and central controlling forms of intelligence are too big and too slow.” (48)

In contrast to the authoritarian and centralized systems that characterized industrial capitalism, the new logic values distributed and non hierarchical systems that adapt quickly to change. According to Gee (2000), “intelligence -control- in distributed systems leaks out of any ‘head’ -centre- and is distributed across relationships; relationships of parts ‘inside’ the system to each other as well as to the ‘outside’ environment or context.” (46) The emergence of this kind of distributed systems changes not only the way in way information, knowledge, and culture are produced and distributed, but also how we imagine and design learning environments for schools and classrooms.

New Literacies, Sociocultural Practices, and Participatory Cultures

Understanding literacies as social practices of meaning making, scholars such as Lankshear, Knobel, Ito, and Jenkins, have studied the emergence of new literacies in the transitional context of contemporary late capitalist societies and the development of digital networked technologies (particularly in the USA). According to them, as young people experience their everyday lives immersed in a complex and interconnected rich media environment they are developing new literacies. As the media ecology of young people becomes richer, more diverse, and interconnected, new forms of digital media production and social media have started to proliferate. For instance, teenagers with access to mobile devices and computers equipped with editing and publishing software, are sharing, modifying, remixing, and circulating digital media assets such as photos, songs, videos, and games through online networks. For young people growing up in contemporary late capitalist societies, media production is part of their everyday life.

This kind of production and practice has become very social thanks to the way in which media is interconnected, and in particular, thanks to the existence of the Internet, a network of networks. As Ito et al. (2009) have argued, “networked media add to the creative production process by providing opportunities to circulate work to different publics and audiences and to receive feedback and recognition from these audiences.” (251) Young people has become engaged in active creation of online content through the making and development of blogs, wikis, websites, social network sites profiles, image and video collections, and forums, where they can interact, collaborate, and share with other peers and mentors. Because media production is embedded in a public social ecology of ongoing social communication, especially among peers, teenagers have earned authority over their own learning and literacy. In their ethnographic study of USA teenagers, Ito et al. have demonstrated that this kind of media production and

peer-based culture among youth is characterized by a new kind of learning that is interest-driven. Young people, participating of this culture, are structuring their learning around their own individual passions for creating media.

In “Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century” Jenkins et al. (2006) have also studied the kind of informal learning that is taking place in contemporary media culture, a culture that they have described as participatory. As Jenkins et al. state, participatory culture emerges “as the culture absorbs and responds to the explosion of new media technologies that make it possible for average consumer to archive, annotate, appropriate, and recirculate media content in powerful new ways.” (8)

The emphasis in participation highlights the connection across educational practices, creative processes, community life, and democratic citizenship. By studying and identifying social skills and competences such as play, performance, simulation, appropriation, multitasking, distributed cognition, collective intelligence, judgment, transmedia navigation, networking, and negotiation, Jenkins et al. describe the opportunities for learning and participation that the “new media literacy” practices are creating. According to Jenkins et al, this new practices can be conceptualized as different forms of participatory culture such as affiliations (membership in online communities, message boards, online games), expressions (music remixing, fan videomaking, fan fiction writing, mash-ups), collaborative solving-problem (working together in teams, formal and informal, to complete tasks and develop new knowledge), and circulations (podcasting, blogging).

The proliferation of new literacy practices among young people needs to be understood, therefore, in relation to a specific cultural, historical, and technological context in where the creation and sharing of media content has become more social, democratic, and networked. Ito et Al. describe this moment as transitional, a moment of “interpretive flexibility with regard to literacy and genres associated with the creation of digital music, photos, and video.” (248)

This moment is also characterized by a participatory culture that, according to Jenkins et al., is one with relative low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement; with strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations with other; with some type of informal mentorship whereby what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices; and where the members feel some degree of social connection and believe that their contributions matter.” (7)

References

Jenkins, Henry et al. (2006) Confronting the Challenges of a Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century. Chicago: The MacArthur Foundation.

Gee, J.P. (2000) “New people in new worlds: networks, the new capitalism and schools.” In Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (Eds.) Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. London: Routledge.

Ito, M. and Lange, P. (2009) “Creative Production.” In Ito, M. et al. Hanging Out, Messing Around, and Geeking Out. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. 243-293

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2011) Digital Remix: The New Global Writing as Endless Hybridization. In Literacies : social, cultural and historical perspectives. New York : Peter Lang. P. 311-332.

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M (2007a) “Sampling ʻthe Newʼ in New Literacies.” In Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. A new literacies sampler. New York : P. Lang.

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M (2007b) Researching New Literacies: Web 2.0 practices and insider perspectives, E- Learning and Digital Media, 4(3), 224- 240.

Lankshear, C., & Knobel, M. (2006). New literacies: Everyday practices and classroom learning. 2nd ed. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.